A tour of V8: object representation

This article has been translated into Chinese. Thanks to liuyanghejerry!

In the previous article, we looked at V8's baseline code generator, the full compiler. Before we move on to Crankshaft, the optimizing compiler, it is helpful to understand how V8 represents objects in memory.

Overview

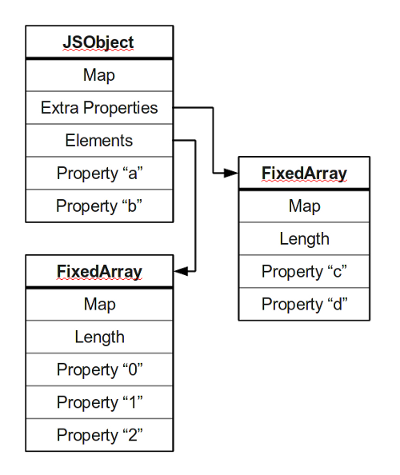

A simple diagram is probably the best way to give a quick overview of the object representation.

Most objects contain all their properties in a single block of memory ("a", and "b"). All blocks of memory have a pointer to a map, which describes their structure. Named properties that don't fit in an object are usually stored in an overflow array ("c", and "d"). Numbered properties are stored separately, usually in a contiguous array.

This diagram only covers the most common, optimized representation. There are several representations to handle different use cases, so if you're interested in finding out more, keep reading.

Some surprising properties of properties

V8 has it's work cut out: the JavaScript standard allows developers to define objects in a very flexible way, and it is hard to come up with an efficient representation that works for everything. An object is essentially a collection of properties: basically key-value pairs. You can access properties using two different kinds of expressions:

obj.prop obj["prop"]

According to the spec, property names are always strings. If you use a name which is not a string, it is implicitly converted to a string. This may be a little surprising: if you use a number as a property name, it gets converted to a string as well (at least according to the spec). Because of this, you can store values at negative or fractional array indices.

obj[1]; //

obj["1"]; // names for the same property

obj[1.0]; //

var o = { toString: function () { return "-1.5"; } };

obj[-1.5]; // also equivalent

obj[o]; // since o is converted to string

Arrays in JavaScript are just objects with a magic length property. Most properties in arrays tend to be named after non-negative integers. length returns the largest integer name plus one. For example:

var a = new Array(); a[100] = "foo"; a.length; // returns 101

Arrays are otherwise no different from normal objects. Functions are also objects, but in their case, the length property returns the number of formal parameters.

Dictionary mode

Since a JavaScript object is basically a map from strings to values, why not just represent them with hash tables? This works fine, and V8 actually uses hash tables to represent "difficult" objects which the optimized representations (detailed below) don't work for. However, accessing a hash table is much slower than accessing a field at a known offset.

Let's talk about how strings and hash tables work in V8. There are many different ways to represent a string, but the most common for property names is a flat ASCII string, where all characters are stored contiguously with one byte per character.

0: map (string type) 4: length (in characters) 8: hash code (lazily computed) 12: characters...

Strings are immutable, except for the hash code field, which is lazily computed. Strings which are used to access properties are symbols, which means they are uniquified. If a non-symbol string is used to access a property it is uniquified first.

Hash tables in V8 are large arrays containing keys and values. Initially, all keys and values in a hash table are undefined (a special value). When a key-value pair is inserted into the hash table, the key's hash code is computed, and the low bits of the hash code are used as the initial insertion index. If there is already a key at that index, the hash table attempts to insert into the next index (modulo length), and so on. Here are pseudocode algorithms for insertion and lookup:

insert(table, key, value):

table = ensureCapacity(table, length(table) + 1)

code = hash(key)

n = capacity(table)

index = code (mod n)

while getKey(table, index) is not undefined:

index += 1 (mod n)

set(table, index, key, value)

lookup(table, key):

code = hash(key)

n = capacity(table)

index = code (mod n)

k = getKey(table, index)

while k is not null or undefined

and k != key:

index += 1 (mod n)

k = getKey(table, index)

if k == key:

return getValue(table, index)

else:

return undefined

Since symbol strings are unique, and hash codes for strings are computed at most once, computing the hash code and comparing keys for equality are fast operations in the common case. However, these routines are still non-trivial, and executing them every time you read or write a property is slow. V8 will avoid using this representation whenever possible.

Fast, in-object properties

In his introductory video from 2008, Lars Bak (who led the team that created V8) describes a faster representation which can be used for most objects. Consider the following constructor:

function Point(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

Constructors like this are the most normal thing in the world. The vast majority of the time, objects created by the same constructor have the same set of properties assigned in the same order. Since these objects have regular logical structure, we can give them regular structure in memory as well.

V8 describes the structure of objects using maps. You can think of a map as a table of descriptors, with one entry for each property. Map contain other information as well, like the size of the object and pointers to constructors and prototypes, but we're mainly concerned with descriptors. Objects with the same structure will usually share the same map. Fully constructed instances of Point might share a map like the following:

Map M2 object size: 20 (space for 2 properties) "x": FIELD at offset 12 "y": FIELD at offset 16

Now you might be concerned that not all instances of Point will have the same set of properties. When a Point is first allocated (before the code in the constructor executes), it has no properties, and the map M2 does not accurately describe its structure. Additionally, we could add a new property to a Point object any time after the constructor executes.

V8 handles this with special descriptors called transitions. When adding a new property, we don't want to create a new map for the object if we don't have to; we'd rather use an existing map if one is available. Transition descriptors point to these other maps.

<Point object is allocated>

Map M0

"x": TRANSITION to M1 at offset 12

this.x = x;

Map M1

"x": FIELD at offset 12

"y": TRANSITION to M2 at offset 16

this.y = y;

Map M2

"x": FIELD at offset 12

"y": FIELD at offset 16

In the example above, a new Point object starts out with map M0, which has no fields. On the first assignment, the object's map pointer is set to M1, and the value x is stored at offset 12. On the second assignment, the map pointer is set to M2, and y is stored at offset 16.

What if a new property is assigned later, to an object with map M2?

Map M2

"x": FIELD at offset 12

"y": FIELD at offset 16

"z": TRANSITION at offset 20

this.z = z;

Map M3

"x": FIELD at offset 12

"y": FIELD at offset 16

"z": FIELD at offset 20

If that property has never been assigned before, we create M3, a copy of M2, and add a FIELD descriptor to it. We also add a TRANSITION descriptor to M2. Note that adding a transition is one of the only ways a map can be modified; maps are mostly immutable.

What if properties are not always assigned in the same order? For example:

function Point(x, y, reverse) {

if (reverse) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

} else {

this.y = x;

this.x = y;

}

}

In this case, we end up with a tree of transitions rather than a chain. The initial map (denoted M0 above) has two transitions; which one is taken depends on whether x or y is assigned first. Because of this divergence, not all Point objects will have the same map.

This is where things start to break down. V8 can handle minor divergences like this just fine, but if your code assigns all sorts of random properties to objects from the same constructor in no particular order, or if you delete properties, V8 will drop the object into dictionary mode, where properties are stored in a hash table. This prevents an absurd number of maps from being allocated.

In-object slack tracking

You might be wondering how V8 knows how much memory to reserve for an object. Obviously, we don't want to reallocate objects every time a new property is added. We also don't want to reserve a big chunk of memory for tiny objects. V8 uses a process called in-object slack tracking to determine an appropriate size for instances of each constructor.

Initially, objects allocated by a constructor are given a generous amount of memory: enough for 32 fast properties stored within the object. Once a certain number of objects have been allocated from the same constructor (8, last time I checked), V8 checks the maximum size of these initial objects by traversing the transition tree from the initial map. New objects are allocated with exactly enough memory to store this maximum number of properties. The initial objects are also resized using a clever trick. When the initial objects are first allocated, their fields are initialized such that they appear to the garbage collector to be free space. The garbage collector doesn't actually treat them as free space, since the maps specify the size of the objects. However, when the slack tracking process ends, the new instance size is written to maps in the transition tree, so objects with those maps effectively become smaller. Since the unused fields already look like free space, the initial objects don't need to be modified.

Now I'm sure your next question is, "what happens when a new property is added after in-object slack tracking is complete?" This is handled by allocating an overflow array to store the extra properties. The overflow array can always be reallocated with a larger size as new properties are added.

Methods and prototypes

JavaScript does not have classes, which means method calls work very differently than in C++ or Java. Methods in JavaScript are just regular old properties. In the example below, distance is just a property of Point objects. It points to the PointDistance function. Any JavaScript function can be called as a method and can access properties of its receiver, this.

function Point(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.distance = PointDistance;

}

function PointDistance(p) {

var dx = this.x - p.x;

var dy = this.y - p.y;

return Math.sqrt(dx*dx + dy*dy);

}

If distance were treated like a normal in-object field, this would obviously waste a lot of memory, since every Point object would have an extra field that points to the same thing. This cost would be higher for objects with a lot of methods. We can do better.

C++ solves this problem with v-tables. V-tables are arrays of pointers to virtual methods. Every object of a class with virtual methods has pointer to the v-table for that class. When you call a virtual method, the program loads the method's address from the v-table and branches to that address. In V8, we already have a shared data structure that can fill a similar role: maps.

To make maps behave like V-tables, we need to add a new kind of descriptor: constant functions. A constant function descriptor indicates that an object has a property with a certain name, and the value of that property is stored within the descriptor itself, rather than in the object.

<Point object is allocated>

Map M0

"x": TRANSITION to M1 at offset 12

this.x = x;

Map M1

"x": FIELD at offset 12

"y": TRANSITION to M2 at offset 16

this.y = y;

Map M2

"x": FIELD at offset 12

"y": FIELD at offset 16

"distance": TRANSITION to M3 <PointDistance>

this.distance = PointDistance;

Map M3

"x": FIELD at offset 12

"y": FIELD at offset 16

"distance": CONSTANT_FUNCTION <PointDistance>

Note that a transition can only be followed to a map with a constant function descriptor as long as the function being assigned is the same one in the descriptor. So if the programmer reassigns the PointDistance variable to a different value, the transition won't work anymore, and we'll have to create a new map. Note that we don't generally load constant functions directly out of a map like we do with v-tables; instead, optimized JavaScript code checks whether an object has a particular map, and if it does, we know it has a particular constant function. A pointer to the function is embedded directly in optimized code.

JavaScript provides another way to work around the problem of shared properties. Every constructor has a prototype object associated with it. Instances of a constructor behave as if they have all the properties contained by their prototypes. Our example could be rewritten as follows:

function Point(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

Point.prototype.distance = function(p) {

var dx = this.x - p.x;

var dy = this.y - p.y;

return Math.sqrt(dx*dx + dy*dy);

}

...

var u = new Point(1, 2);

var v = new Point(3, 4);

var d = u.distance(v);

This is extremely common. It's also the canonical way to implement inheritance, since each prototype object may have its own prototype object. The instanceof operator operates on the prototype chain.

As with regular objects, V8 will represent prototype methods using constant function descriptors. Calling prototype methods may be a little bit slower than calling "own" methods because the compiled code has to check not only the receiver's map but also the maps of its prototype chain. This probably won't make a measurable performance difference though and shouldn't impact the way you write code.

Numbered properties: fast elements

So far we've discussed normal properties and methods. We've assumed that for instances of the same constructors, the same properties get assigned in the same order, most of the time. This may not be the case for numbered properties (elements accessed with array indices), and since any object can behave like an array we need to treat these differently. Remember, according to the spec, all property names are strings, and other values are converted to strings before they can be used as keys.

We will define an element as a property whose key is a non-negative integer (0, 1, 2, ...). In V8, elements are stored separately from named properties. Each object has a pointer to its elements, and the object's map indicates how the elements are stored through the elements kind field. Note that maps don't contain descriptors for individual elements, but they may contain transitions to otherwise identical maps with different elements kinds. Most commonly, objects have fast elements, which means that elements are stored in a contiguous array. There are three different fast elements kinds. In order of increasing generality, they are:

- fast small integers

- fast doubles

- fast values

According to the spec, all numbers in JavaScript are 64-bit floating point doubles. We frequently work with integers though, so V8 represents numbers with 31-bit signed integers whenever possible (the low bit is always 0; this helps the garbage collector distinguish numbers from pointers). So objects with the fast small integers elements kind only contain this type of number. If we want to store a fractional number or a larger integer or a special value like -0, then we need to upgrade the array to fast doubles. This involves a potentially expensive copy-and-convert operation, but it doesn't happen often in practice. fast doubles objects are still pretty fast because all of the numbers are stored in an unboxed representation. If we want to store any other kind of value, e.g., a string or an object, we must upgrade to a general array of fast elements.

JavaScript doesn't provide any way to specify how many elements an object will contain. You can say, for example, new Array(100), but this only works for array objects. If you store a value to an index which doesn't exist, V8 will reallocate the elements array and copy the old elements to the larger block of memory. V8 can handle arrays with "holes": elements that haven't been defined between those that have. Internally, a special sentinel value is stored in these locations, so you get the undefined value when you load such a property.

Of course there are limits to what you can do with fast elements. If you assign to an index that's way past the end of your the elements array, V8 may downgrade the elements to dictionary mode. In this representation, elements are stored in a hash table. This is useful for sparse arrays, but there is a significant performance cost, both in converting a fast elements array to a hash table and in accessing the elements later. If you're copying an array, you should avoid copying from the back (higher indices to lower indices) because this will almost certainly trigger dictionary mode.

// This will be slow for large arrays.

function copy(a) {

var b = new Array();

for (var i = a.length - 1; i >= 0; i--)

b[i] = a[i];

return b;

}

Because named properties and elements are stored separately, even if an object drops into dictionary mode for elements, named properties may still be accessed quickly (and vice versa).

Conclusion

In this article, we looked at how V8 represents objects and their properties. V8 provides a general interface for objects and switches between appropriate data structures depending on usage. This adaptability a real advantage that virtual machines have over compiled languages; other languages must either deal with sub-optimal performance or require the programmer to explicitly specify how objects should be represented.

In the next article, we'll look at V8's optimizing compiler, Crankshaft, and how it takes advantage of in-object properties and fast elements to generate efficient code.